Are small and medium states ready to stop terrorists with cryptocurrency?

Cryptocurrency, or “crypto” as some prefer to call it, is slated to be the future of financial transactions. While the further development of crypto is widely celebrated, with mild speculations, traceability remains the most important issue surrounding the digital currency that requires abject focus. Often, acute discussions about the pros and cons of cryptocurrency assume that the higher financial forces will always be able to bring the necessary and sufficient security in the system, deterring both state and non-state actors from weaponizing the digital currency. However, it is crucial to assess how much authorities have done to include the use of cryptocurrency by terrorists in their anti-money laundering schemes, and how far terrorist actors are willing to go incorporate crypto as an alternative financing within their systems.

Debunking the Crypto myth – what is it?

Cryptocurrency is a transaction that takes place independent of a central authority. It uses a distributed public ledger called blockchain, which is a record of all transactions and is available to everyone. This means, crypto is decentralized, does not operate under any state’s authority, and provides almost instantaneous fund transfers with zero fees. A common myth often told is that crypto is untraceable. Perhaps, its decentralized nature and a general lack of understanding contribute further to this mystique. For many of us average Joes living in small and medium states, and even some policymakers, this myth automatically translates to either “controlled use of crypto is the future” or the much-dreaded “crypto will ruin the world” – most falling on the latter basket.

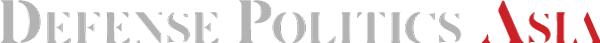

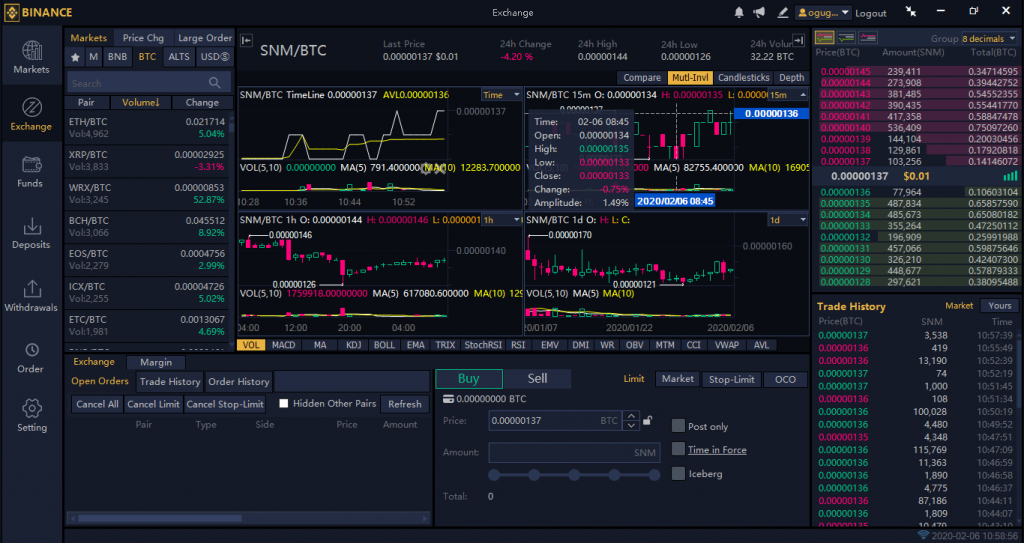

Crypto is hosted on commonly accessible ledgers, which means that everyone has access to records of each transaction irrespective of who made it and where it was made. The identity of the person who transferred a lump sum is represented by a “hashed ID,” followed by a series of numbers. This means, although one cannot find the identity of the people involved by analyzing a single transaction, dedicated pattern analysis can potentially lead to the discovery since a publicly accessible ledger allows state authorities to trace crypto flows. However, as it is with all detection of crimes, the two most crucial element required in the mix is the awareness that a crime is happening, and the political mobilization required to stop it.

On Political Will

An acute awareness of illegitimate crypto use looks like a widely agreed upon recognition that the tool can be a viable alternative financing channel that connects a transnational terrorist network headquarters in the Middle East, or supposedly anonymous global and regional donors of terrorist causes, to local hubs in the small and medium states. In countries where crypto is not outright banned, it is largely ignored in the system and mentions often make it to the annual risk assessment’s recommendations list.

For instance, Bank Indonesia’s (Central Bank of Indonesia) Payment System Blueprint 2025[1] recognizes that the advent of cryptocurrency runs the risk of spurring increased money laundering and terrorist financing through ownership of digital assets, yet the nascent cybersecurity laws remain largely absent from steps safeguarding the use and ownership of cryptocurrency in terrorist financing. In the Philippines, the Anti-Money Laundering Council particularly noted the use of cryptocurrency in its Terrorism and Terrorism Financing Risk Assessment 2021[2], citing suspicious transactions associated with bitcoins or virtual currency worth PhP1.77 million between 2019 and 2020. The report also mentions anecdotal incidents of terrorist groups using crypto assets in the Marawi siege, yet the Philippines digital laws allow cryptocurrencies to be used as a legal tender, effectively enabling users to convert crypto into fiat currency through ATMs of the Union Bank of Philippines.

Internationally, guidelines to prevent the misuse of crypto to finance terror activities have been led by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) who published updated guidelines[3] in 2020 for virtual assets and virtual asset service providers. It identifies the gaps in the security infrastructure of nations, and seeks to ensure a common standard. In this regard, Indonesia is only an observer of the FATF, with the Philippines on the brink of being included in the grey list due to “strategic deficiencies” in its money laundering and terrorism financing system[4]. On top of this, adhering to the spirit of the guidelines and implementing is a major challenge and one that is especially difficult for small and medium states in the developing world who prioritize spending to prevent conventional forms of terrorist financing. Most importantly, states’ affinity to prioritize monitoring of traditional financing exposes the gap between the political will to completely nip extremism in the bud, and the terrorist ambition to live and fight stronger another day.

Characterizing A Terrorist’s Ambition and Strategy

Terrorist organizations have centralized decision-making and decentralized execution. This means any innovation in the grand strategy of a terrorist group is always designed by the top brass of the leadership[5]. This looks like Wadie Haddad’s influence on the PFLP to adopt airline hijacking as a critical move[6] in the fight against Israeli occupation, or Osama Bin Laden’s push to shift focus away from the near enemy in the Middle East, to the far enemy that is the United States[7].

Almost all instances indicate a top-down process of adopting innovation in grand strategy, where individual leaders with strong personalities and authoritarian leadership styles played pivotal roles in important decision-making processes that changed the identity of the organization[8]. While terrorist leadership always appears open to suggestions from their subordinates, it is often that only the execution is left to the lower-level recruits who occupy the local hubs.

Financing for local terrorist hubs in small and medium states pours in from all over the world, especially from the Middle East. The funding does not flow to metropolitan hubs, like Dhaka or Jakarta. Rural areas, where it’s much easier to influence radicalism and recruit the pawns for execution, become primary recipients.

Rural Radicalization

Rural areas in Bangladesh, for instance, have historically exhibited higher forms of radicalization[9] with money going to religious institutes like madrasas and Islamic study circles which promote fundamentalist ideologies. Parents who send their children to these institutes often cannot afford to feed or educate their children. So, the madrasas provide food, clothing, and basic education. As a result, parents become loyal to these madrasas as they feel left out by the state, conjuring up a feeling that the religious institutes are safe havens for their families and their collective community. In Indonesia, terrorist recruiters, especially in the rural regions draw on poor democratic performance to justify the violent pursuit of alternative systems of governance. Most recruits foray into terrorism through the Islamic Study Circles[10], which are categorically shaped like madrasas in Bangladesh, with many of them teaching an extreme brand of Islam to young children from a very young age.

Perhaps the most important piece in the operations puzzle is characterizing the terrorist entrepreneurs within the leadership circles of local hubs. Looking at Dhaka’s Holey Artisan attacks in 2016, one of the two masterminds – Tamim Chowdhury – is a Bangladeshi-born Canadian with an undergraduate degree in Chemistry from the University of Windsor. Tamim was allegedly tasked to coordinate between the Islamic State and the local hub, Neo-JMB (previously known as Jamaat al-Mujahideen, Bangladesh), supplying financial help, weapons, conducting recruitment and the radicalization process of the operators of Holey Artisan attacks.

The five militants tasked to carry out the attacks come from upper-middle class backgrounds, with some being recent dropouts from renowned international universities, studying engineering and science subjects. An International Crisis Group (ICG) report published in 2018 indicates that a vast diversity in recruitment has been observed, targeting more urban youths who are students of mainstream education at private universities. Just by virtue of their backgrounds, the evidence indicates that it is highly likely terrorist actors in the rank and file are abreast of the technological advancements and more willing to be the first ones to adopt cryptocurrency and increase operational efficiency in their financial transfers.

“Easier Money”

The case is simple: even a pseudo-anonymous transfer allows these actors to mask various financial transactions – both from the transnational network headquarters or from generous local and regional donors – and allocate resources accordingly. What is a bigger cause for concern is that cryptocurrency reduces the likelihood or assigning a middle-man for financial transactions, which both Al Qaeda and the ISIS have historically employed. The financial ease also rings the ominous bells since it will not require the local hubs to be geographically confused to a certain region anymore. This means, Neo-JMB will not have to restrict their footprints in the mountainous terrains near Bangladesh’s border with West Bengal, just to ensure cover for their middleman as they bring in cash and a meagre weapons supply, but apply the faster mode of alternative financing to explore into other regions as well and spread their recruitment missions.

Possibly the best example of a first-mover advantage came in May 2020, when the Philippine Institute for Peace, Violence and Terrorism Research (PIPTVR) reported the first-ever cryptocurrency transaction made by the Islamic State-backed local hub under the Filipino government’s nose, with the funds allegedly directed towards Jemaah Ansharut Dalauh and Mujahideen Eastern Timur activities in the conflict-ridden Mindanao region of the southern Philippines. The money laundering operation had crypto of “suspicious origin” channelled through unidentified exchanges, to make tracking difficult.

Inevitable evolution

The assumption we make is that the traditional framework of terrorist financing will always exist, but the ease of access in setting up “potentially” untraceable cryptocurrency transactions will compound a local hub’s strategy of bypassing the adversary’s web of defense, dismantling the resource constraint that once dominated the operational calculus of these transnational non-state actors. If there’s anything the changing character of war suggests, it’s that transnational terrorist networks are always on the lookout to find strategic advantages. In this case, working through financial tools left largely unmonitored by state apparatus might prove costly. One might look at the use of crypto in Mindanao and call it a rarity, others may argue for stringent regulations. But it’s undeniable that terrorists will experiment with cryptocurrency to rejuvenate their activities, and policymakers can decide if they want to catch-up or catch-on-the-act.

Bios

Asif Muztaba Hassan is an independent journalist based in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Shamsul Nawed Nafees is working as an analyst for a renowned multinational consultancy.

Additional editing by Wyatt Mingji Lim

[1] Bank Indonesia. “Indonesia Payment Systems Blueprint 2025 // .” Indonesia Payment Systems Blueprint 2025. Accessed January 24, 2022. https://www.bi.go.id/en/fungsi-utama/sistem-pembayaran/blueprint-2025/default.aspx.

[2] Anti-Money Laundering Council. “Terrorism and Terrorism Financing Risk Assesment 2021.” Republic of Philippines Anti-Money Laundering Council , n.d. http://www.amlc.gov.ph/images/PDFs/2021%20JAN%20TF%20RA%20EXECUTIVE%20SUMMARY%20(WEBSITE).pdf.

[3] Financial Action Task Force. “Guidance for a Risk-Based Approach.” Accessed January 24, 2022. https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/recommendations/RBA-VA-VASPs.pdf.

[4] Arianti, V., and Kenneth Yeo Yaoren . “How Terrorists Use Cryptocurrency in Southeast Asia.” The Diplomat. The Diplomat, June 30, 2020. https://thediplomat.com/2020/06/how-terrorists-use-cryptocurrency-in-southeast-asia/.

[5] Moghadam, Assaf. “How Al Qaeda Innovates.” Security Studies 22, no. 3 (2013): 466–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2013.816123.

[6] Ibid

[7] Ibid

[8] Crenshaw, Martha. “Innovation: Decision Points in the Trajectory of Terrorism.” Essay. In Terrorist Innovations in Weapons of Mass Effect: Preconditions, Causes, and Predictive Indicators. Maria Rasmussen and Mohammed Hafez (Defense Threat Reduction Agency Advanced Systems and Concepts Office, 2010.

[9] Rep. IN-DEPTH STUDY ON RADICALIZATION FACTORS IN RURAL, URBAN, UNIVERSITY AND DETENTION ENVIRONMENTS IN FIVE REGIONS OF NIGER, 2018. https://www.ndi.org/sites/default/files/English%20Translation%20of%20Key%20Sections%20of%20the%20NCSSS%20Study%20on%20Radicalization%20Factors%20in%20Niger.pdf.

[10] Idris, Iffat. Rep. Youth Vulnerability to Violent Extremist Groups in the Indo-Pacific, 2018.