Thai Junta’s Election Victory: What does it mean for the country political future?

The election of General Prayuth Chan-o-cha, for what has essentially become a second term for the Junta’s administration, might have come as a surprise to many. However, given the results of the 2019 national election, the Junta’s return to power was rather obvious.

While many news outlets often categorise the winners of the 2019 election into groupings of “Democratic”, “Pro-Junta” and “Undeclared”, the fact that Thailand is a country where bitter political rivalry run rampage meant that voters would either view the presented party as either populist “Red” or conservative “Not-Red”. In a country, fractured by political in-fighting, there is only “us” or “them”, no space is given for those who wish to not be a part of such bipartisan politics. There is perhaps no better example than the humiliating defeat of the Democrat Party who lost more than half of their voting electorates when the they declared that they would not support the Junta’s rule.

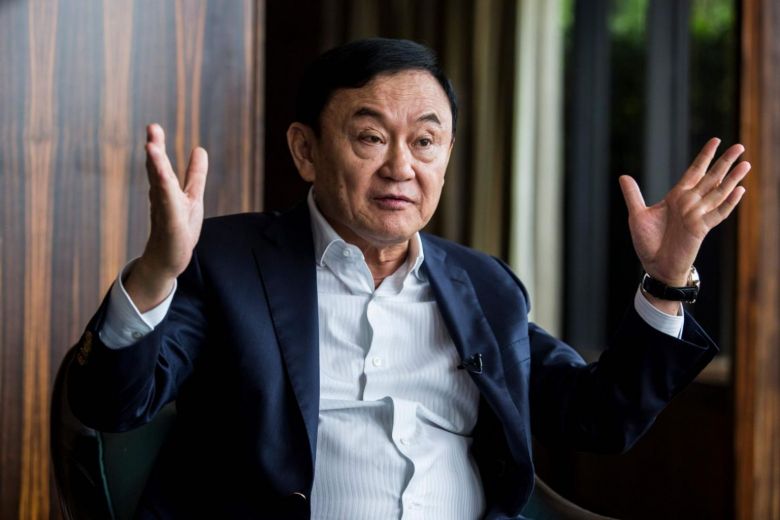

While the pro-democracy coalition did attempt to distance themselves from Mr. Thaksin Shinwatra, the former Prime Minister-in-exile, many conservative voters were evidently convinced of the two leading parties of the coalition, the Future Forward Party (FFP) and Pheu Thai Party (PTP), connections to the former PM in-exile. Many of both parties’ MPs and candidates were drawn from previous associations of, or even subordinates to, Mr. Thaksin. This assumption is not entirely without basis.

Thus while, the key member of the Junta’s coalition like the Democrat and Bhumjaithai Party have not declared their association with the pro-Junta Phalang Pracharat Parties (PPP) – the fact that these two have had a long history of resisting the Thaksinean dominance in politics (and even leading the mobs that paralysed the business district in the country capital just a few years prior) should speak volumes to many conservative voters.

This author believes that it was inevitable from the beginning that the two parties would eventually join the pro-Junta coalition. Anything less would be akin to political suicide for the two.

However, despite the overwhelming parliamentary support for General Prayuth’s PM candidacy, the Junta leadership of the country is still in a deeply precarious position. And here is why;

The Mechanic of the Parliamentary System

The parliament of Thailand has finally elected General Prayuth Chan-o-cha as the new Prime Minister of the country, after a succession of meetings and a month-long period of deliberations. With the overwhelming parliamentary vote for the support of the Junta’s leader (500) to that of the Thaksinean democratic coalition (246), it might seem that the power over legislation would lie firmly in the pro-Junta’s coalition hands.

However, nearly half of this large margin of supporters come directly from the Senate. A self-appointed body that isn’t a popularly elected candidate. The Senate, holding distinct roles and responsibilities from the MPs, in which the latter plays a much more important role in the day-to-day running of the legislative arm.

The Thai parliament is divided into two sections. The 500 members of elected MPs, and the 250 self-appointed Senate members. The senatorial body was formed by the politically neutral technocrats who represent the various experts and specialists from across the spectrum, from industries to scientific and educational bodies.

In addition to the well padded Curriculum Vitae of many individual Senators, they are required to have at least 10 years of experience in the field of their professions, and must not be a member of political party, in a ministerial positions, or a career employee in the government (with the exception of all the heads of the military branches and policing bodies who will have seats reserved in the Senate).

While the self-elected Congress is supposed to be neutral, it is undeniable that this body acts in full support of the Junta and the ruling technocrats. For instance, the Senate’s qualifications are noticeably more relaxed for former government employees than the elected politician. Individuals who previously served in political offices or is a member of a political party are banned from serving in the Senatorial positions, they have to wait for at least 5 years after their absence from any of the aforementioned offices to be eligible. However, No such requirements were mentioned for the candidate who was a previous government employee.

This means that governmental candidates may exploit this loophole and quit their job to join the Senate, even as early as just a year prior, allowing them to retain a close connection and influence within their previous official capacities. A clear conflict of interest and a question of neutrality. And yes, this also extends to military personnel who are natural allies to the Junta.

And if that wasn’t obvious enough, the Senators who served in the first 5 years of their office, must also receive the approval by the Junta’s main governing body, the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO.)

Unsurprisingly, nearly the entire Senate voted for General Prayuth. However, this also means that the actual number of MP who voted for the Junta’s leader only account for 250 or so seats (254 to be precise) as opposed to the previous 500 figures. These numbers are far less clear-cut compared to the 246 opposition votes for Mr Thanathorn of the FFP’s candidacy.

Why do these matter?

While the Senate can vote for the country’s premiership, their legislative power is otherwise quite limited compared to the MPs. Voting for a new bill, for instance, is solely eligible only for elected MPs. And while the Senate can request the bill to be sent back for review, they cannot veto it, and if pressed, the bill will be passed with or without the senatorial consent.

This MP-exclusive power also includes functions like issuing and voting in motions of no-confidence. With a large portion of MPs in the Junta’s coalition consisting of candidates from the none-Junta affiliated political parties like the Democrat and the Bhumjaithai Party – General Prayuth’s administration will be at the mercy of the two mid-size parties for anything, from day-to-day legislative function to surviving a no-confidence debate. Without the unanimous support from the Democrats and Bhumjaithai Parties, the PPP-led coalition will have no hope of getting any of the legislation passed.

The Uneasy Alliance

The Democrat and Bhumjaithai Party’s support came at a price.

Should they agree to join General Prayuth’s Administration,

the two parties were promised ministerial positions in the “A-class” governmental departments in return. These include places in the Ministries of Transport, Public Health, and Tourism and Sport for Bhumjaithai. The Democrats will get places in the Ministries of Commerce, Agriculture and Cooperatives, Social Development and Human Security, as well as the right to the constitution amendment.

These offers are indeed generous for a minority within the larger PPP-dominated coalition. However, at the time of writing, the PPP has started to show signs of not being willing to follow through on the promises they made.

According to Somsak Thepsuthin, MP and leading member of the PPP party. The PPP would like to retain, at least a ministerial seats in the Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives which is the key area where the party had promised to their own members. The MP also mentioned that the arrangement of the ministers in the government will have to ultimately be subjected to General Prayuth’s own review regardless of the earlier promises.

While the Bhumjaithai and Democrat leaders remain confident that the PPP will honour their agreement prior to the deliberation, this development could result in a significant rift in the ruling coalition should the agreement be broken.

If the two coalition parties become dissatisfied with the outcome of the post-deliberation agreement, it can easily snowball into a political crisis. If even as little as a dozen MPs from any of the two minority parties are to vote against the PPP majority within the coalition, the opposition can easily win a motion of no-confidence which only requires a half of votes. The 250 strong Junta-affiliated Senate will have no means of intervening.

In such an event, General Prayuth may retaliate against this move with the dissolution of the parliament, in turn forcing the country to hold another election.

This process makes the incumbent extremely vulnerable to political crises. Such precedence is the leading cause of coups (sometimes from the ruling military themselves to restore absolute control to the government).

The Haunted History and Evolution

Coups and hostile military takeovers have always been a staple of Thai history. Since the abolition of the absolute monarchy in 1932, the country experienced over 30 coup attempts from the military, often due to the weakness of the elected civilian government with no clear majority; leading to a round after round of a motion of confidence debates and parliament dissolutions. Ultimately, making them vulnerable to the ever present threat of the ambitious military commanders.

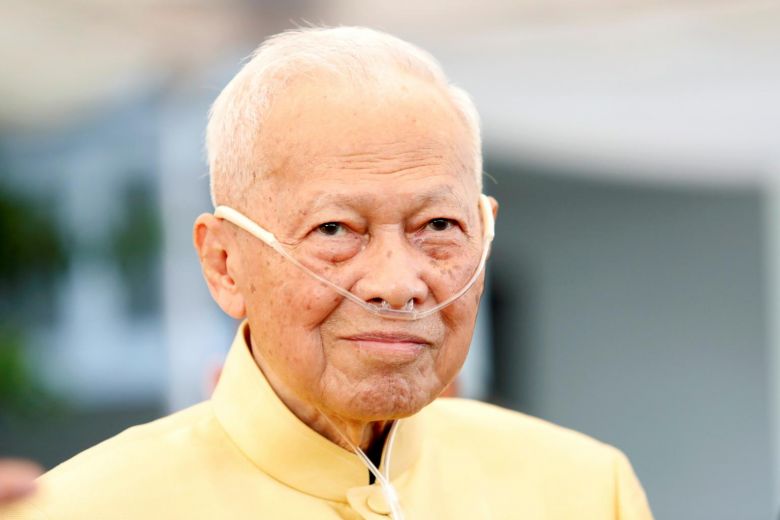

In the 80s, the cycle of crisis was finally broken by a new brand of politics pioneered by the highly respected General Prem Tinsulanonda. Outside of Thailand, General Prem was best known as one of the region’s major wartime leader who resisted the Vietnamese aggression in mainland Southeast Asia. Within the country, however, the recently deceased General was a deeply respected statesman who engineered one of the most effective systems of government in Thailand’s political history.

Rather than depend on the absolute might of the military, General Prem’s method of governance was more system-driven and can function even without the participation of the military. By forging a strong alliance with the country’s ruling bureaucrats, the palace, and the military leadership, it ensured that in the event of a military revolt against his administration, the government can still depend on the other political institutions to restore control and ultimately defeated the rebellious coup leaders. As demonstrated by the administration’s success in defeating two coups and several assassination attempts by the military, for the first time after decades of the golden age of Junta’s power.

In essence, this was a technocracy where qualified bodies of individuals and experts were given precedence over elected civilian representatives. Yet, it ultimately gave the senior General’s administration something that the Juntas of the past could never grasp – a perception of legitimacy and a unified system of governance that did not rely solely on the whims of a powerful military commander.

The coming of Mr. Thaksin Shinawatra and his system of popular (if authoritative) democracy, however, completely changed the political landscape that happened as the result of General Prem’s system of technocracy. Unlike the weak, democratically elected governments of the past; Mr. Thaksin’s political party was powerful, perhaps the strongest civilian government this country ever witnessed.

His populist policy made him initially extremely popular to both the urbanites and rural electorates. This translates into an almost single party parliamentary domination which, to this date, remains unprecedented in the country’s long and turbulent history.

With this landslide victory, Mr. Thaksin introduced, what is effectively the polar opposite to General Prem’s technocracy. Under Thaksin’s Administration, the ruling technocrats were significantly undermined, replaced by the loyal allies and the personal network of Mr. Thaksin’s own business associates. This effectively granted him and his associates a direct control over Thailand’s political institutions.

The system of the ruling rich presiding over the poor masses may sound dystopian or even Orwellian in nature. Yet, Mr. Thaksin’s skilled management of Thailand’s economy and governmental organisations made him one of the most economically successful political figures in the country.

His invasive intervention of the country’s bureaucratic system and institution, however, had made him extremely unpopular not only to the old technocrats but also the urban conservatives who previously voted for him. As it was, the conservative campaign on the streets to get rid of Mr. Thaksin’s old administration had become the genesis of the bitter rivalry between the conservatives and the populists, and the mob tactics that haunts Thailand to this day.

Yet, despite the seemingly recurring theme, there is something fundamentally different in the Conservative vs Populist conflicts of the past (the original Yellow vs Red shirts) and the schism today. While old grudges, like the rumours of Mr. Thaksin’s and his successor’s republican tendencies, had always played a role in the conservative, anti-populism rhetoric – it was his intrusive intervention and almost a dynastic approach to governance that triggered a notable reaction. To put it into perspective, Mr. Thaksin has been ousted because he was ‘undemocratic’. While the military intervention was welcomed in the end, ironically it was never the goal of many original protesters.

Indeed, over the years, preventing the return of ‘Thaksinism’ seems to be the focus of many conservative mobs – many of which were direct against Mr. Thaksin’s proxies (like his younger sister who also lives in exile after the 2014 coup). However, despite some of the consistent grievances (i.e. corruption), the pretext that Mr. Thaksin and his “Thaksinean” political allies being “undemocratic” seem to have been abandoned entirely by the conservatives in the recent discord.

In fact, the current NCPO-led administration resembles the original Thaksinean administration in many ways. The heavy reliance on populist policies to win over the masses and the intrusive approach of appointing close allies to the positions of power, all of these were practices that prompted the original conflict with the Thaksinean factions by the conservative. Today, many of the PPP politicians are even allies and politicians from the Thaksinean parties of the past themselves.

In the author’s own opinion, as one of the people who witnessed the genesis of the original conflict between the Conservative and the Populist, the line between the conservative and the populist politicians has started to become blur in the recent times, perhaps as early as the ousting of Mr. Thaksin a decade ago.

This represents a worrisome development as even though Mr. Thaksin and his allies had begun to lose importance in the recent conflict, the song of ice and fire within the context of Thai politics somehow manages to fuel itself. Even when the original tinder was all but gone.

This coupled with the general lack of faith in democracy (perhaps even on both side of the conflict) suggests that Thailand is about to step into a new page of history, one that may witness even more turbulence than the previous page.

Cover image: Thai flag raised during the recent election

- Thailand's military-backed PM voted in after junta creates loose coalition

- การเมือง เลือกตั้ง 62 l รัฐธรรมนูญ 2560: ส.ส.-ส.ว. ทำอะไรได้บ้าง

- สมาชิกวุฒิสภา 250 คน มาอย่างไรและทำอะไร Official government material on the role and origin of the Senate of Thailand

- 30 ปี การสิ้นสุดของระบอบเปรมาธิปไตย (2) : 8 ปี 5 เดือน ของนายกฯ เปรม ภายใต้การเมืองสามเสา

- พรรคพลังประชารัฐขยำใหม่ โควตารัฐมนตรี ยึดกระทรวงเกรดเอ

- ‘Ministry deals’ in tatters – Palang Pracharat revoke cabinet post promises

- Smile and wiggle: Thai PM Prayuth tries to charm his way to a win

- ELECTIONPalang Pracharat still quibbling over portfolios in the new Thai parliament

- PM Lee sends condolence letter on death of former Thai premier Prem Tinsulanonda

- Exiled former premier Thaksin says Thailand's election 'rigged' by junta