To South Korea, Is Japan Actually A Military Threat?

After invading twice in the 1590s and colonizing its neighbor throughout 1910~1945, is it really still possible for Japan to pull it off? Does it even have the desire to do so?

Having a deep interest in all things related to the military (from history, equipment, tactics, doctrine, organization and so on) since elementary school, as a child I sometimes wondered how a modern total war between South Korea and Japan would look like. Growing up in the Korean community, hearing comparisons – and at times derogatory remarks and insults – towards Japan wasn’t uncommon, whether that be in sports, politics, history and so forth. In the Internet, it could reach to rather unkindly lengths.

It did however, spark the question – is Japan actually a military threat that South Korea should be concerned about today and in the future?

As far as politics and war regarding Korea and Japan are concerned, the history goes back well over a millennium ago. The first of such was during the Three Kingdoms Era in the Korean Peninsula, where one of the Korean kingdoms known as Baekje maintained a military alliance with Japan (known as Wa at the time) to fight against its rivals Goguryeo and Silla on two separate occasions.

Artist’s depiction of the Battle of Baekgang, where a joint Baekje and Wa (Japan) force fought against the Tang Chinese and Silla. Image source – Tistory

Later on in the era of the Joseon Dynasty during the 1590s, Japan outright invaded the entire peninsula twice. It very nearly succeeded on its first attempt, being only hampered by Ming Chinese reinforcements on land and the brilliant naval victories pulled by the Korean admiral Yi Sunshin, who is largely considered a national hero in South Korea today for his efforts.

Notably, his most well-known achievement is the Battle of Myeongnyang, which effectively sealed the fate of Japan’s invasion efforts in the later days of the war.

Battle of Myeongnyang, 1597, where a squadron of merely 13 Korean warships under Admiral Yi stood against the Japanese fleet of up to at 130 vessels. Despite overwhelmingly outnumbered, the Koreans attained a strategically decisive victory and devastated the Japanese fleet. Image source – Antique Alive

Fast-forward to the first decade of the 20th century, Japan outright colonized Korea, first as a protectorate in 1905 and then finally annexing it entirely as part of its empire in 1910. In the years that followed all the way up to 1945, the Japanese military and various Korean resistance groups would fight what can be best described as a low-intensity conflict in China, though the two sides would also battle in other countries during World War Two.

Now, it is 2019.

Seventy-three years have passed since the end of the Second World War. It has been also over fifty years since they have also formally normalized diplomatic relations.

Although Korea and Japan have not shot at one another out of anger since then, relations between the two have been complicated, to say the least in recent years. This is very much due to grievances dating back to the Japanese colonial period during the first half of the 20th century, which does not seem to see any signs of being permanently settled and dealt with anytime soon.

Adding onto this is the territorial dispute between the two countries – namely the Dokdo/Takeshima issue which has consistently been a thorn into the two countries’ relations. From the South Korean perspective, there is even a belief that the islands will come under attack by a certain ‘external force’ (specifically, Japan) and perhaps as far as used as a staging point for invading the Korean peninsula itself, despite the unlikelihood of it happening at all.

This has gone to the extent that South Korea conducts field exercises around the island twice a year, with the objective being defending it against a hypothetical Japanese incursion.

ROK Air Force F-15K Slam Eagles make a pass during South Korea’s field exercise dedicated to defending Dokdo/Takeshima in 2018. Image source – FMKorea

Complicating matters further are the recent disputes in where a South Korean destroyer was alleged by Tokyo to have locked its fire-control radar on a Japanese naval patrol aircraft on December 20th, 2018, in which both sides failed to settle their differences. Following this is the accusations by Seoul that Japanese patrol aircraft flew overhead at a low level above South Korean warships on two separate occasions in January 18th and January 22nd respectively, considering them as acts of provocation.

Aside from the fact that these incidents saw South Korean-Japan relations take a serious hit, this notably the first time they were affected by an incident of military nature.

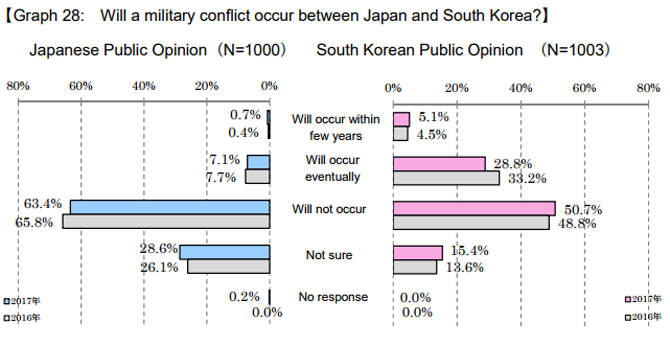

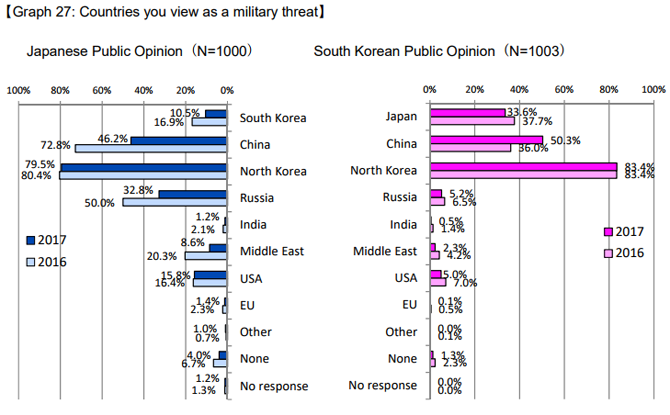

Perhaps most surprisingly however, is that in relatively recent polls (albeit long before the above-mentioned incident) a significant number of Koreans see Japan as a military threat and even see conflict with Japan as a very possible reality somewhere down the future.

Image source – Genron NPO

Based on Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s (as well as some others who served in under his administration) controversial views and intentions regarding the country’s defensive stance and its own history during the early 20th century though, it should not come as much as a surprise that the average Joe and Jane in South Korea would see Japan as a potential military threat.

However, that then raises the question – is Japan actually a threat to the Republic of Korea? And if so, can it actually successfully invade and conquer it like it almost did in the 1590s and turn it into part of some kind of neo-Japanese empire as its imperial predecessor had during 1910~1945?

This article will provide and explain four major reasons why this is unlikely.

1. South Korea does not even register as a military threat to Japan’s national security.

It is really quite telling when Japan’s 2018 White Defense Paper makes no mention of the Republic of Korea as being considered anything even remotely close to being a threat to Japan’s own national security or a target of interest for Japan’s military buildup. One can even access the paper’s section detailing on the Korean Peninsula, where it clearly considers North Korea to be one of the two legitimate military threats (the other being the People’s Republic of China) to Japan’s national security, not South Korea.

Unsurprisingly, it is North Korea’s military capabilities take up the bulk of the topic of that particular section overall, given the obvious missile threat it poses.

As the image shows, Japan falls under the range of North Korea’s short and intermediate-range missiles. Image source – Associated Press

This is further backed by the fact that Japan’s response to this is the purchasing of the Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defense system, which is set to come online in 2023, along with plans to deploy two new guided missile destroyers equipped with the Aegis BMD system to bolster its current fleet of Kongo and Atago-class destroyers. Both ship classes also are equipped with the Aegis system as part of Japan’s ballistic missile defense network against North Korea (and to an extent, China).

To get a basic idea of how Japan’s BMD shield is supposed to function, refer to this image below;

According to Taiwanese media on January 2019, Japan was also reportedly considering the deployment of THAAD to further boost its ballistic missile defense shield. Image Source – The Mainichi

While South Korea does have its own arsenal of ballistic missiles, namely the Hyunmoo 2B and 2C, with a range of 500km and 800km respectively, much of these are positioned to strike targets (particularly missile launch sites) in North Korea as part of its Kill-Chain strategy. There is no evidence to suggest that the ROK has anything planned that’s of the same nature towards Japan and that is assuming such even exists in the first place.

Additionally, procurement of military equipment such as over 100 F-35 stealth fighters (of which 45 are the STOVL F-35B variant), refitting the Izumo-class ‘helicopter destroyers’ into aircraft carriers and deployment of assets (primarily anti-air and anti-ship missiles and combat aircraft) and personnel around Japan are primarily a response to the growing naval and air capabilities of China, as well as its increasingly assertive posture regarding not only territorial disputes with Japan but also the wider Asia-Pacific region as well (this also applies to Russia to a lesser degree).

This is further proved by the numerous amounts of intrusions Japan has been scrambling against Chinese and Russian aircraft as of late.

![[âIMG]](https://1.bp.blogspot.com/-HL2Odl48slw/XLhWLzZQv0I/AAAAAAAAJKc/iyHHItxpaOgbKdD-tterw-UBcrzHBAhjgCLcBGAs/s1600/scrambleshurray3.jpg)

![[âIMG]](https://3.bp.blogspot.com/-GyoZ3XJUPpU/XLhVpP_vBsI/AAAAAAAAJKQ/KeWcbxnQ3q8ty1pcL2AtI0pcRNTLgApugCLcBGAs/s1600/scrambleshurray2.jpg)

Assuming the ‘other’ interceptions are towards ROK aircraft, this still heavily pales to those of Chinese and Russian intrusions and they certainly have not gotten the attention of Japanese media and political leaders. Image Source – Space Battles

Japan’s military is also geared not only countering both North Korea’s missiles and China’s growing naval power but also on expanding the country’s geopolitical influence across the Asia-Pacific region in an effort to contain the latter. There is a reason why Japan had deployed its naval forces in the South China Sea with the US 7th Fleet while it had also been investing heavily in the economy of ASEAN states. Even Prime Minister Abe himself has clearly been public with this as early as October 2018.

Considering South Korea does not even fit into any of this, it would make one wonder why anyone would think Japan is considered a military threat. With the North Korean missile threat as well as the constantly growing power of China’s military, it would be ill-thought for Japan to add South Korea into the list of security concerns it faces.

2. The Japan Self-Defense Forces simply are not up to the task of actually successfully invading South Korea

In spite of Japan’s intentions to strengthen its military posture, there are numerous reasons as to why the Japan Self Defense Forces lack the ability to pull off what its predecessors had long ago.

The major issue is that Japan simply does not have the means to deploy enough troops and equipment to be able to not only land in Korea in substantial numbers but also knock the ROK military out of the fight as well. To further break this down, the problems Japan would face are these three reasons down below.

. Inadequate Transportation

The Japan Maritime Self Defense Force (JMSDF) does not have an adequate amount of ships to transport the required number of ground troops into Korean shores and hold ground. Currently, the JMSDF possesses three Osumi-class amphibious transport docks and nine landing craft though this has evidently been inadequate, considering Japan was reported to be looking at the possibility of purchasing transport ships to be under the GSDF for moving troops and material. Even so, this rather small fleet is nowhere near enough to really attempt an invasion on a scale similar to that of over four hundred years ago.

Likewise, the Japan Air Self Defense Force (JASDF) only has a few dozen transport aircraft available for carrying troops, equipment, and supplies across distances that helicopters cannot cover. This is hardly enough to sustain an invasion on Japan’s neighbor to the west while also operating in hostile airspace against a near-peer adversary whose air force isn’t all that far off (if not arguably equal or even superior in some respects) in overall capability with the JASDF.

JASDF C-1s lined up for take-off. With a fleet of just a little over a dozen C-103 Hercules and 20+ C-1s and new but fewer C-2 airlift aircraft, the JASDF would be far-stretched to support the logistical needs of a hypothetical invasion on the Korean peninsula. Image Source – J-HangarSpace

While the JASDF and JMSDF may have enough assets to transport the land forces needed to seize small remote islands far away from Japan’s home islands in a rapid manner, it is inadequate for committing to a full-fledged invasion on Korea.

In a war against the Republic of Korea, much of the JMSDF and JASDF will be operating much closer to and within hostile waters and airspace, where the potential of significant material losses will be extremely high, if not even arguably outright unacceptable.

. Lack of required force projection on land.

The Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF) currently has only one brigade – the Amphibious Rapid Deployment Brigade, which numbers 2,100 troops and expected to reach 3,000 in the near future – that specializes in amphibious operations. This is a major capability that is a vital requirement for projecting force via sea – and one Japan still lacks when it comes down to the numbers necessary to establish a firm grip on South Korean soil.

The brigade, for example, is equipped with just a little over fifty AAV-7s to carry troops to the shores and a number of MV-22 Ospreys and CH-47 Chinooks for air transport – yet has little in the way of artillery, armor and anti-tank weapons, all crucial for operations in South Korean soil.

Another two units that can be used for projecting force – specifically from the skies – is the 1st Airborne Brigade and the 12th Air Assault Brigade.

But much like its larger amphibious counterpart, the 1st Airborne Brigade and 12th Air Assault Brigade are relatively small formations (the 1st Airborne itself consists of no more than 1,900 personnel and the 12th Air Assault numbering 4,000) and lack the necessary firepower to stand on their own against heavier and significantly larger ROK forces.

The locations of ROK Army divisions (active and reserve) circa 2016. Not included are armored, artillery and commando brigades on the corps-level, the Army’s special forces brigades, and the ROK Marine Corps’ two divisions. As of 2019, some divisions have been disbanded and merged with others. Image Source – Naver Blog

Regardless if Japan’s airlift capability can ferry the whole brigade or only a portion of it over South Korean skies, it doesn’t negate the strong likelihood that the unit will not only be seriously in danger of being overwhelmed by significantly larger numbers of ROK forces on the ground but also incredibly difficult to supply and support before any reinforcements can link up with them.

Even with plans to change a significant number of its current standing forces into rapid-reaction units and turn the overall ground forces into a much more agile fighting organization as mentioned above, the JSDF simply does not have enough transportation capability on its own in both land and sea to pull off a successful large scale invasion on Korean soil and slugging it out against ROK forces.

Additionally, the overall organization and disposition of Japan’s ground forces heavily suggests that much of it is not geared for expeditionary warfare on a scale capable conquering whole countries (let alone Korea), as shown by this map below;

The Ground Self Defense Force, as shown in this map, is divided into five regional armies totalling 9 divisions (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th and 10th) and 6 brigades (5th, 11th, 12th, 13th, 14th and 15th), along with the Amphibious Rapid Deployment Brigade and 1st Airborne Brigade that operate separately. Image source – Ministry of Defense

For enough troops to be assembled for such an invasion would require significant preparations in transporting large numbers of troops, supplies, and equipment, as well as training them for actual combat scenarios against ROK forces. At the same time, however, concentrating such a large number of not only land but also air and naval assets for an invasion on the ROK will undoubtedly leave Japan much more vulnerable to its larger neighbors such as China.

At best, Japan’s most optimistic chances are if its objectives are rather limited, such as seizing Dokdo/Takeshima isles or even the southernmost island of Jeju, which has a major ROK naval base.

This latter is considered a vital hub for South Korea’s ambitions to expand its naval presence beyond its own borders in the future. Seizing this island would be a massive setback on South Korea’s geopolitical aspirations, as well as potentially even outright controlling its access to the wider Pacific Ocean and beyond.

Republic of Korea Navy warships docked at Jeju Military-Civil Naval Base. Image Source – OhMyNews

Even so, this also is highly unlikely given the base is also a site for American naval vessels to prepare for military drills with their South Korean counterparts and possibly other allies too. Additionally, due to the strategic importance the base is to South Korea there is also the strong possibility it will be heavily defended and further reinforced before even it is attacked. Such an attempt would also likely be a costly venture not just militarily but also politically.

. Long-term Manpower Shortage.

The entire strength of the JSDF in 2018 was reported to be just over 220,000 (with approximately 138,000 in the GSDF, and roughly 42,000 each in the ASDF and MSDF). Despite increasing recruitment of women and loosening of age restrictions for enlistment, the JSDF is likely to see its manpower decline in the foreseeable future as the country’s population continues to age and shrink, affecting the pool of recruitable candidates significantly.

To make matters more difficult, roughly 37% of the JSDF’s personnel are reported to be aged over 40 and recruitment targets quotas have never been reached since 2014. If things weren’t hard enough already, competition with the private sector in the midst of a relatively stable economy has also made it more difficult to recruit eligible men and women into the force.

Below are two graphs that show just how much of a contrast the JSDF’s age demographics are to say, its US counterpart and how hard it has been affected by the population decline and competition with the private sector;

![[âIMG]](https://abload.de/img/japanmilitraltereedk0.png)

![[âIMG]](https://abload.de/img/japanmilitralter26se17.png)

Although Japan intends to make efforts in somewhat minimizing the understaffing it has by increasing efforts on developing its capabilities on artificial intelligence, drones, and robots, the shortages in manpower will still be felt in the years to come. After all, at the end of the day, even with automation there will still be a demand for humans to keep warships, aircraft, armored fighting vehicles and artillery maintained in working order at sufficient levels, as well as to keep them staffed at adequate levels to ensure operational readiness rates are not compromised.

Even if Japan somehow miraculously manages to somehow subdue South Korea and successfully annexes the country like it did in the past, it would still need a substantial amount of troops and equipment committed to just occupying it.

At its current strength, this is simply not feasible. Another major issue facing Japan in this unlikely scenario would also be that it’d also have to contend with sharing a physical border with North Korea – a rather undesirable situation that would undoubtedly stretch its forces – particularly those on land – quite thin.

3. A Massive ‘Hostage’ Problem

Perhaps what should be most concerning to Japan is that are as many as nearly 60,000 Japanese residing in Korea itself at any given time. Should an all-out or even limited conflict between the two nations occur, the safety of those people cannot be guaranteed. Although Japan reportedly was developing plans on how to evacuate its citizens in the event of a war breaking out in the peninsula, this more than likely was in response to the scenario of hostilities between South Korea and North Korea resuming. Not one where South Korea and Japan would be fighting one another.

In the event of attempting an invasion as some in South Korea may fear, Japan would inevitably put the lives of its own citizens in the country at serious danger of retaliation. Further fuelling this is the noticeable anti-Japanese sentiment within the country, where protests are not unheard of and in more bizarre cases, local governments proposing listing Japanese companies as war criminals and have stickers labeling them as such on any of their products used in their areas (while such nonsensical plans were not fully welcomed, the fact they were even planned for by the country’s leaders is discerning).

Worse, the government of the Republic of Korea in the past has shown to be more than capable of committing appalling atrocities in wartime and for political reasons, some that would not seem all too different to what Japan had done in its destructive path of imperialism beforehand. Such examples are the Bodo League Massacre where at least 100,000 civilians suspected of being communists were executed, as well as the massacre of pro-democratic protestors in Gwangju and the rape of tens of thousands of women during the Vietnam War.

This photo was taken by US Army Major Abbot showing a political prisoner just moments away from likely execution by South Korean authorities, 1950. Image Source – Wikipedia

Even as late as 2016, the country’s armed forces were reported to be planning to deploy thousands of troops (including special operations forces) and armored vehicles against its own populace during the widespread protests against then-President Park Geunhye. Had the protests gone the wrong way and the plan was indeed executed, there is little doubt as to what the outcome likely would have been.

This map shows the planned locations of deployment of troops, tanks and APC/IFVs from the 20th and 30th Division to the Blue House, Central Government Complex, Constitutional Court of Korea, the National Assembly and Gwanghwamun Gate against the mass candlelight protests towards then-president Park Geunhye. Image Source – Yonhap Graphics

Should a conflict between Korea and Japan happen, there is very little that the JSDF can really do for what is essentially tens of thousands of hostages at the mercy of the host nation they’re residing in. Although one can argue that Japan could use this for propaganda purposes to boost domestic support and morale, at the same time, this also has the potential to politically backfire immensely.

While the present government of South Korea certainly is not the same as its predecessors of previous decades, war between the two neighbors certainly can very likely transform anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea into something multitudes worse.

4. The United States will not just sit by idly

This is arguably the biggest reason why Japan is simply unlikely at all to ever think about trying to repeat another attempt on Korea.

Both South Korea and Japan are vitally important allies of the United States in the Asia-Pacific region and have been so since the 1950s. Both are also heavily dependent on the presence of US forces in their soil, given the missile threat posed by North Korea and an increasingly assertive China whose geopolitical interests and growing military strength don’t exactly align eye-to-eye with the Japanese and South Koreans.

The last thing the United States would ever want – and likely prevent at all costs – is a war fought between its two most strategically important allies in Asia. An attempt by Japan on attacking South Korea or vice versa, would by extent also bring US forces in both countries in very real danger of being caught in the crossfire and that is something the US simply won’t let slide so easily. Even more so, there’s up to a total of approximately over 60,000 US military personnel in the two countries, including several major bases.

One should also consider that both the South Korean and Japanese armed forces are strongly integrated to operate with their US counterparts as well. It is also not uncommon to hear of joint training exercises occurring. These exercises are not small by any measure; those such as Keen Sword and Foal Eagle typically involve at the least tens of thousands of troops each on land, air, and sea.

And while rarely heard of or given attention to, the United States also holds trilateral military exercises with South Korea and Japan, further showing its interest in ensuring the two neighbors work together against a common threat regardless of whatever historical animosities they have.

.jpg)

The aircraft carrier USS George Washington alongside a ROKS Chungmugong Yi Sunshin-class and a JMSDF Shirane-class destroyer in joint naval drills in 2012. Image Source – Global Military Review

As such, the scale of such exercises should give a good idea as to just how much of an important role the United States plays in the national security of the two East Asian neighbors, making it further unlikely for either Japan or South Korea to engage in an all-out war against each other, let alone even an isolated incident of shooting out of anger.

The only countries that would really benefit from such a scenario would be China and North Korea, for it is in their interest to see relations between South Korea and Japan to deteriorate and thus, weaken US influence in East Asia (and by extension may also affect Southeast Asia indirectly). In essence, one could argue that the presence of US troops within Japan and Korea is an absolute necessity to prevent even the slightest possibility of conflict between the latter two nations occurring.

Conclusion

Ultimately, it is rather preposterous to believe Japan would ever pose an actual credible military threat to South Korea or has any intention of being so. Any laughable suggestion that it does – subtle or direct – is little more than paranoia at best. At worst, it would be fear-mongering for domestic consumption purposes, which certainly likely is the case with the current South Korean and Japanese administration.

As explained above, Japan’s military forces even in the wake of recent developments to its overall capabilities are not geared towards South Korea, nor does the country even consider its neighbor to be of much worth the cost of (if at all) going to war against.

The fact that South Korea also does not measure as an actual country of strategic interest for Japan’s overall national security in its defense white paper, followed by the overall defense posture of the JSDF and the reasoning behind its procurement and development of various equipment further backs this. Even if that isn’t the case, the Republic of Korea’s military is more than capable enough to hold its own against an attempted Japanese invasion. One cannot stress enough that Korea today isn’t the same vulnerable country as it was in the dying days of the Joseon Dynasty in the late 19th century and the dawn of the 20th century or in the 1590s.

Japan’s and South Korea’s alliance with the United States, as well as their integration with the US military also is another major reason that shouldn’t be overlooked or taken lightly.

Ultimately, a war between the two nations is in neither’s interest. There should not be any perceived belief that it will happen and even if that likelihood increases, both countries need to realize that there is very little to gain from deteriorating relations.